Belief

Unless we are strictly debating the underlying empirical validity of UFOs (between the MHH and OEH hypothesis) we cannot “believe in UFOs”. This notion contradicts the generally accepted definition of a UFO by indirectly equating them with extraterrestrial spacecraft.

The same logic applies to the idea of whether “UFOs are real”, which is indisputable, as the thousands of monthly reports to organizations such as MUFON and NUFORC indicates. The notion of belief should be kept within discussions of theory and implications of the phenomenon. If unchecked, this phrasing lets pass unspoken assumptions about the nature of UFOs and warps the context of our conversations, hindering our the goals towards greater understanding.

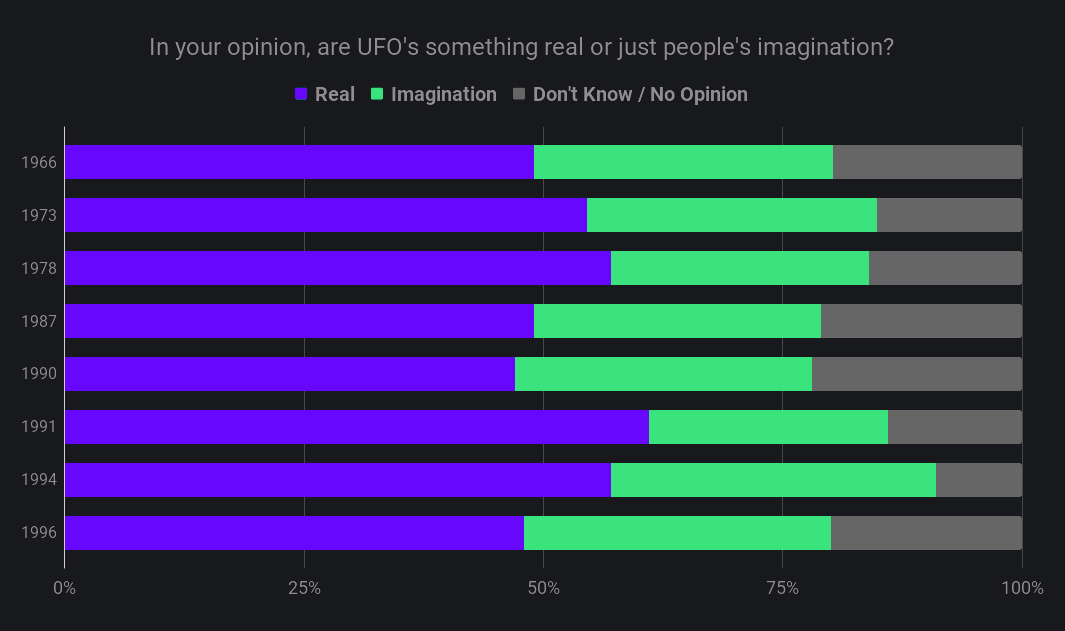

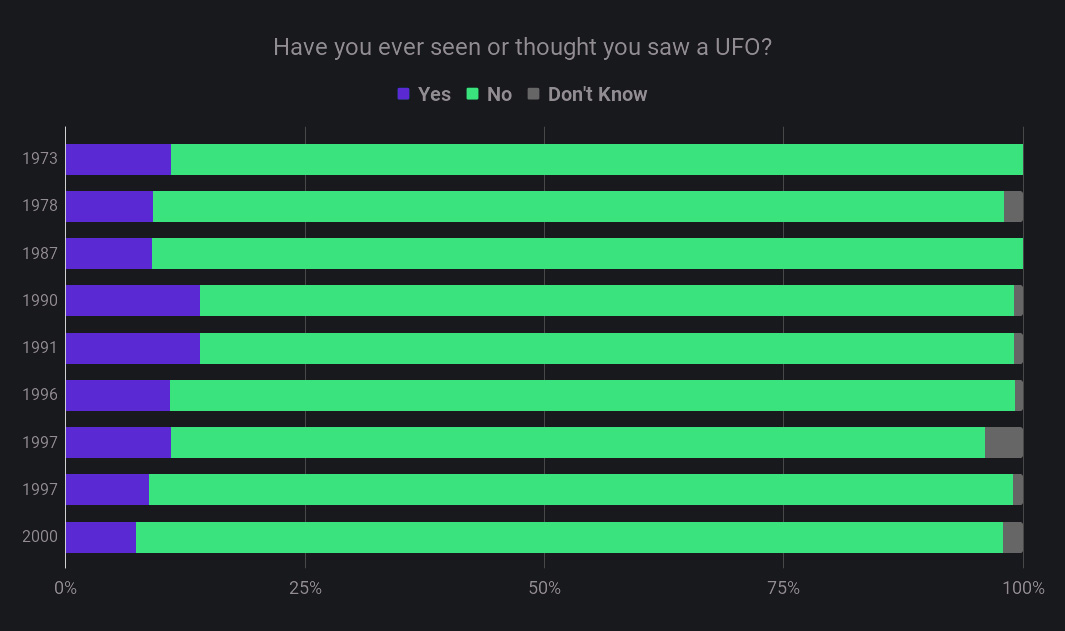

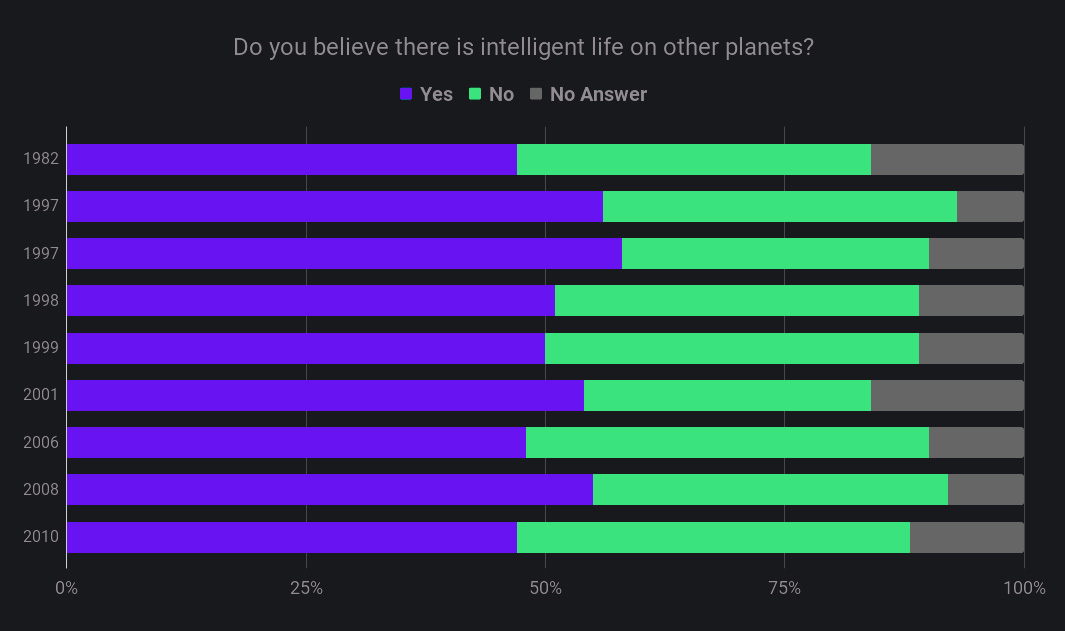

Many polls have been taken within the United States regarding the public opinion on UFOs since the 1970s. A paper from the Asian Journal for Public Opinion Research titled Paranormal Beliefs: Using Survey Trends from the USA to Suggest a New Area of Research in Asia (2015) was written by a team of professors from the US, Korea, and the associate director of research at the Pew Research Center. They sought to gather poll data to encourage sociological research in Asian countries, and their findings covered a variety of paranormal phenomena. Their results showed public beliefs regarding the nature of UFOs has remained relatively consistent throughout the last four decades:

This data was pulled from a variety of different organizations. Question wording and sample size varied throughout.

View the paper if you’d like a more detailed view of the data.

Appeal of Belief

“UFO cultists are influenced not by the objective facts of a situation but by their interpretation of those facts. They act according to what they believe, not according to what might actually be true. The fact that their interpretations may be grossly inaccurate does not prevent them from behaving as if they were correct. This is what Vallée means when he says that ‘contact with space may become a social fact a long time before it is a scientific reality.’ “ – David Swift

A variety of psychological factors can contribute to our desire to form specific beliefs involving UFOs:

- Need for feelings of uniqueness by displaying scare knowledge.

- Need for meaning in the absence of religious beliefs.

- Fear of changing times and social conditions.

- Desire to transcend the fear of death, embodied in the promise of travel to another physical level.

- Boredom and feelings of inadequacy in the human condition.

- Desire to escape everyday responsibilities.

- Desire to interpret evidence favorable to our existing beliefs or misinterpret evidence unfavorable to them.

These are only a few examples, and the fundamental reasons obviously vary between individuals. Although, the most devout groups of believers have existed since the 1960s and impacted society in a myriad of ways. David Swift, a professor of sociology at the University of Hawaii, elaborates on the topic in the epilogue to Jacque Vallée’s Messengers of Deception (1979):

At present, contactee groups are small, and have no obvious effect on society, except for discrediting serious research into the UFO phenomenon. But will this situation remain the same? What are the circumstances under which these cults could become broad social movements, posing a real challenge to society? Such movements arise when many people feel frustrated by existing conditions, and when the movement gives hope for improvement. These hopes may seem far-fetched to an outsider, but there is practically no limit to the irrationalities which may be associated with a successful movement. The factors that affect social movements in general have been summarized in The Handbook of Social Psychology:

The ultimate success of social movements does not depend on their size or organization, or the quality of their leadership, or the sophistication of their views. It depends, rather, on the extent to which they successfully express the feelings, resentments, worries, fears, concerns, and hopes of large numbers of people, and the degree to which these movements can be viewed as vehicles for the solution of widespread problems.

UFO cults appeal to a vast audience. The problems they address are an undeniable fact of our times. Profound changes have affected everyone, particularly in the Western world. Science, technology, and education have undermined traditional beliefs, but have not provided satisfactory substitutes. “God is dead”; yet nothing has taken his place to guide us, reassure us, and protect us. Families have shrunk nearly to the vanishing point. It is the rare person who still lives in the same house or community as his grandparents did. Few of the hundreds of people we pass on the streets know who we are, or care. Old occupations, practiced by generations, suddenly become extinct; skills developed by a lifetime of practice become worthless. And over all these social and psychological concerns loom the threats of environmental pollution and energy crises, and the very real possibility that nuclear war will bring an apocalyptic end to life on this planet.

There is widespread uneasiness about these problems, and various remedies are being offered, including meditation, political action, drugs, and religion. UFO cults are competing with all of these for the support of dissatisfied, disillusioned people. What are the chances that UFOs will outdraw the others? What can saucer sects offer that the rest cannot? A light in the sky, and the message that someone up there can help you.

At first glance this may not seem impressive, but if we think about it we will realize that the UFO has some features which make it a formidable contender.

First, the UFO, more than any of its competitors, highlights the inadequacies of science, the armed forces, and government. These are among the most powerful institutions in our society; yet they are unable to deal with UFOs.

For thirty years the flying saucer has made our leaders look ludicrous. They can’t explain it, they can’t ignore it, they can’t catch it, and they can’t make it go away. It hovers on the edge of public awareness, occasionally darting into the spotlight, creating a moment of consternation, and then withdrawing into the shadows, usually leaving its observers unharmed but shaken by the experience. Physical scientists say that it is a problem for social scientists, and social scientists just as quickly throw it back to the physicists and astronomers. The Air Force, after grappling with the problem for twenty years, tried to wash its hands of the matter in the late 1960s. Although the government denies that UFOs exist, a 1973 Gallup poll found that almost all Americans (93 per cent) were aware of UFOs, and 15 million adults thought they had actually seen one. When the question “Are UFOs real or imaginary?” was asked of the group that was aware of the problem, the percentage of those responding “real” increased from 46 per cent in 1966 to 54 per cent in 1973, and to 57 per cent in 1978, when only 27 per cent responded “imaginary.” No other symbol has so silently but effectively undermined the credibility of our leading institutions.

Secondly, the UFO is a universal symbol, appealing to men and women of many lands, ages, and races. It is not even restricted to a specific period in history. To simple observers, it is a wondrous bauble glittering in the sky. To the more sophisticated, it seems to be a product of a superior technology. In either case, the underlying message is so clear that it hardly needs to be verbalized: the creators of this awesome object have fantastic knowledge and power, and this knowledge and power might help you.

This is an alluring message, and it will become more attractive with each failure of conventional attempts to solve our complex problems. The thought of salvation from the sky is likely to grow in appeal.

This belief is, after all, not so different from traditional religious doctrine. The idea that benevolent beings live in the sky goes back to our childhood, and to the early stages of human society. The UFO simply adds the trappings of modern science to those ancient beliefs. Because of twentieth-century technology, even we humans can fly into the heavens, and the advocates of radio astronomy encourage us to believe that there are civilizations far out in space.

Thus, belief in UFOs is not such a big step, and may well attract large numbers of people who are dissatisfied with more mundane answers to our inescapable problems.

Would such movements be a threat? Quite possibly. They could undermine the rational foundations of society. They would not have to overthrow the present system all by themselves; they could simply reinforce irrational currents that already exist.

Revelation rather than reason is the source of contactee beliefs. This is not a new occurrence. There have been previous periods during which people followed voices rather than logic, superstitious belief rather than observation and experiment, and the consequences were disastrous.

This is one of Vallée’s most telling points. He thinks that UFO sects will be influential because of today’s spreading belief in the irrational. It is to this belief that our institutions are vulnerable. Thus, as he observes, the genuine counter-culture of today is not that of hippies or drugs, but rather the counterculture of UFO contact. It is more durable, subtle, and dangerous because it has a broader social base; it is not tied to any specific group or age bracket.

The irony is that scientists themselves have contributed to this situation by refusing to consider problems beyond the borders of safe, established science. Vallée remarks that the attitude he first observed among his colleagues at Paris Observatory – science’s reluctance to investigate paranormal phenomena – is slowly driving many people to react by accepting any claim of superior or mystical contact.

Vallée himself elaborates within the same book on the general social effects such groups have on society. His thoughts were considerably prescient, considering they were written over forty years ago:

It remains for us to summarize the social effects that the belief in UFOs is likely to create – whether such physical objects exist or not. We have seen six major effects throughout this investigation. They were reflected in personal interviews and in quotations from the books and pamphlets of contactee organizations.

1. The belief in UFOs widens the gap between the public and scientific institutions. Some day our society will pay the price for the lack of scientific attention given the UFO phenomenon. As more and more sincere witnesses come forward with their stories, only to be summarily rejected by the academic or military institutions they thought they could trust, an increasing gap is created. Not only may the public turn away from science in any form (and become skeptical of the value of its investment in energy research and space technology), but it may seek a substitute in new high-demand philosophies and pseudosciences. This movement toward superstition in turn antagonizes the scientists, who cite it as evidence that the UFO phenomenon should not be studied seriously, and the vicious circle continues.

2. The contactee propaganda undermines the image of human beings as masters of their own destiny. Beginning with the idea of Atlantis and of “Chariots of the Gods,” and continuing with Biblical interpretations of Yahweh as an extraterrestrial, contactee literature is replete with suggestions that all the great achievements of mankind would have been impossible without celestial intervention. Should we thank extraterrestrial visitors for teaching us agriculture, the mastery of fire, the wheel, and most of our religious traditions? To anyone who has studied the history of science, such ideas (romantically attractive as they are) appear ill-founded. The best and the worst in human beings have been displayed in all the cultures we know. Early cultures were as gifted for fashioning pyramids and building canals as they were skilled at exterminating their enemies, at raping, and at pillaging. Three thousand years later, we are engaging in the same behavior, although we build canals and exterminate enemies “scientifically.”

3. Increased attention given to UFO activity promotes the concept of political unification of this planet. This is perhaps the most commonly recurring theme in my entire study of these groups. Through the belief in UFOs, a tremendous yearning for global peace is expressing itself. In a way that was captured very early by novelists like Koestler and Newman, the UFO is focusing human attention away from the Earth. Whether this becomes a factor for positive or negative social change depends on the way in which this focused attention is channeled.

4. Contactee organizations may become the basis of a new “high-demand” religion. The current conservative backlash against “decadent” morality and social liberalism has led many to reconsider their spiritual orientation. The Catholic Church is at a critical point in its history, and many other religions are in trouble. The new churches emphasize high standards and strict discipline. The creeds of UFO organizations often emphasize themes of sexual repression, racial segregation, and conservative values that place them in a position to capitalize on the growth of this movement. Especially noticeable in this respect is the attention received by “the Two” and the widespread success of the Melchizedek groups. Inherent in such sectarian activity is the seed of revolutionary religious movements with almost unlimited potential.

5.Irrational motivations based on faith are spreading hand in hand with the belief in extraterrestrial intervention. As the UFO phenomenon develops unchecked, with no expectation that research on its nature will be honestly attempted, a continually growing fraction of the public is becoming convinced that many phenomena are beyond the scope of science and are “unknowable” by rational process. If this fraction becomes the majority, they may end society’s unquestioned support for rational science. Instead we may soon find an intermediate system of beliefs, in which an almost mystical faith in higher “contact” blends together with advanced technology in strange hybrid ways. Among the contactees, the idea that all attempts at scientific control must be given up and replaced by blind faith is already prevalent.

6. Contactee philosophies often include belief in higher races and in totalitarian systems that would eliminate democracy. From the statement that UFOs have visited us in the past, it is only a small step to saying that their occupants have “known” the Daughters of Man, “and found them fair!” Then some of us may have celestial blood in our veins, which would make them “superior, to others. The idea of a “chosen people” is an old one; it had lost its appeal in recent decades. Strong belief in extraterrestrial intervention could revive this primitive concept, with particular groups claiming privileges peculiar to those who descend from the stellar explorers. We have also seen that the alleged communication with UFO occupants, when it touched on political subjects, tended to emphasize totalitarian images. Vorilhon, for instance, reports he was told that democracy was obsolete. Raymond Bernard was instructed to expect a “reversal of the old values.” These six effects of the belief in extraterrestrial intervention indicate that an increase in the social conditioning correlated with the UFO phenomenon may lead to complex changes. If the Manipulators do exist, I certainly salute their tenacity, but I am curious about their goals. Anybody clever enough to exploit the public’s expectation of UFO landings, or even to simulate an invasion from outer space, would presumably realize that human institutions are highly vulnerable to changes in our images of ourselves. It is not only the individual contactee who is manipulated, but the global image in humanity’s collective psyche. One would like to know more, than, about the image of humanity such Manipulators harbor in their own minds – and in their hearts. Assuming, of course, that they do have hearts.